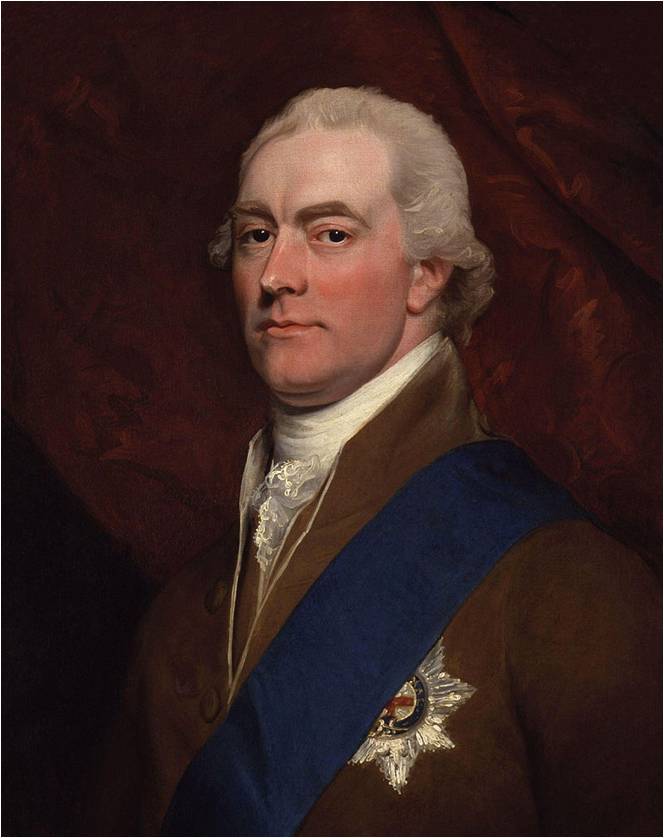

Capability Brown

Historical Notes Regarding Wimbledon Park

by Douglas Gardiner & Timothy Ball

For centuries, the area around Wimbledon has been popular because of its close proximity to London, but more so because of the beauty of the landscape and particularly this lovely valley that makes up Wimbledon Park. As a result, Wimbledon Park has been owned by a succession of wealthy landowners who have built great houses and lavished their money on the landscape.

From about 1280 there was a manor located in Wimbledon. The grapes from Vineyard Hill were used to make wine for the Archbishop of Canterbury, possibly made by the monks from Merton Priory. Horse Close Wood also dates back to the earliest maps and may have formed part of the ancient woodland that once covered this part of London.

Sir Thomas Cecil built the first great house in 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada. The house was built of brick in the Elizabethan style and had extensive formal geometric gardens recorded on a plan made by Robert Smythson in 1609. Thomas Cecil, Earl of Exeter, was the son of William Cecil, Lord Treasurer to Elizabeth I.

The park was enclosed and deer grazed amongst the woods. It extended from Wimbledon Common down to Durnsford Road and covered about 400 acres. There was no lake at this time but there were eight fishponds. James I hunted in the park. In 1638 Charles I bought the manor for Queen Henrietta Maria. She commissioned Andre Mollet to soften the Cecil geometric garden design.

During the Civil War [1640s], many of the park trees were cut down for Cromwell’s ships and poaching depleted the deer. However, after the war, the manor was restored to Queen Henrietta Maria who sold it in 1661 to George Digby, Earl of Bristol.

He employed John Evelyn to redesign the gardens and to add grottoes, fountains and statuary and by the 1670s the gardens were laid out on a magnificent scale. In 1678 the estate was bought by the Earl of Danby, chief minister to Charles II, and then acquired after his death in 1712 by Sir Theodore Janssen, director of the South Sea Company. He tore down the original house and started to build a new one, but this was never finished, presumably due to the bursting of the South Sea Bubble in 1720.

As each owner changed and improved to his or her tastes, there unfolds a history of landscape design, and of patronage of the eminent or fashionable landscape architects of each generation.

By the time Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, purchased the Park in 1728, there was a great avenue leading towards Putney from the house. She demolished the beginnings of Janssen’s house and constructed a new house, set higher up on the crest of Vineyard Hill to take advantage of the views both to the north across the Park and across the southern lawns towards Epsom Downs.

Upon her death in 1744 the estate, which was now about 1,200 acres, passed to her son, John Spencer. Point 4 on the Heritage Trail is the closest we can get to the view from the Spencer House, which was positioned approximately where Ricards Lodge High School is now located. Earl Spencer wanted to improve the view northwards across the valley and so in 1764 employed Capability Brown to change the Renaissance gardens and park into a more natural landscape, known as the Serpentine Style. This is often regarded as the classic English garden.

Brown is the most famous of English landscape designers. He was born in Northumberland and served an apprenticeship with Sir William Lorraine. Having moved to Buckinghamshire he was employed by Lord Cobham at Stowe until 1741. This gave him the opportunity of working with William Kent and John Vanbrugh, so developing his talents as landscape designer and also as an architect. In 1764 he was appointed by King George III as H.M. Surveyor of Gardens and Waters with a large house at Hampton Court.

Brown is the most famous of English landscape designers. He was born in Northumberland and served an apprenticeship with Sir William Lorraine. Having moved to Buckinghamshire he was employed by Lord Cobham at Stowe until 1741. This gave him the opportunity of working with William Kent and John Vanbrugh, so developing his talents as landscape designer and also as an architect. In 1764 he was appointed by King George III as H.M. Surveyor of Gardens and Waters with a large house at Hampton Court.

The Serpentine Style developed by Capability Brown was a reflection of the taste of the time for less formal and more natural shapes in landscape. The essential features were always a view from the house across well kept parkland, to a lake with picturesque clumps of trees, but never enough trees to block the view.

Encircling the park would be dense woodland to frame the views and to conceal the carriage drive.

At Wimbledon, Brown cut down the long straight avenues of trees and laid out a new winding carriage drive from a lodge at Tibbet’s Corner, following the line of modern Victoria Drive and Church Road. Across the valley he built a dam, converting a marshy stream into a thirty-acre lake.

In 1790 Hannah Moore wrote "I did not think there could have been so beautiful a place within seven miles of London. The park has so much variety of ground and is as un-Londonish as if it were a hundred miles out."

A contemporary newspaper article noted that "The grounds about the Lord Spencer’s place at Wimbledon are perhaps as beautiful as anything near London. Nature has done much of it and Brown made it much more."

During the French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars, Wimbledon became a political centre at the highest levels. Because Wimbledon was close to the Portsmouth Road (the A3), access to Portsmouth was easy, which made Wimbledon popular for naval officers. Also, part of the attractiveness of Wimbledon was the prevalent wind from the SW which was invariably free of the pollution that one found in London, particularly during the 18th century. William Pitt the Younger was the Prime Minister during much of this period and he suffered from a lung condition which led his doctors to recommend that he rode his horse away from London for exercise and fresh air. Wimbledon was his frequent destination, only seven miles from Westminster.

Henry Dundas was the Home Secretary and later held the new position of Secretary of State for War. He was a tough Scottish politician who favoured ending the slave trade. He resided in Cannizaro House on Wimbledon Common and was regularly visited by Pitt who arrived on horseback. Also resident on Wimbledon Common was William Wilberforce who was the most important anti-slavery MP. He and Dundas would support each other and then argue and then support each other again until the Slave Trade Act was finally passed in 1807. Pitt also visited Wilberforce regularly and often slept over at his Wimbledon house.

We then have Earl Spencer who was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1794 and his wife Lavinia who resided in Wimbledon Park House, which was regularly visited by Pitt and the leading naval officers of the period including Lord Nelson and his wife Francis. Nelson had two very important naval supporters, Earl St Vincent (Admiral Sir John Jervis) who was Nelson’s commander and Earl Spencer who St Vincent reported to. All was well until Nelson, following his victory at the Nile, became infatuated with Lady Hamilton in Naples. Upon Nelson’s return to England in 1801, and Emma’s buying Merton Place in South Wimbledon, the relationship with Earl Spencer grew frosty as Lavina refused to have anything to do with Lady Hamilton. Nelson became a social outcast, but he cared little as he was more often than not at sea and Emma was the love of his life. It all came to an end at Trafalgar with the death of Nelson in 1805. Pitt passed away in 1806 and Earl Spencer lost his post as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1801, so from there Wimbledon lost its place of importance. Earl Spencer and Lavina moved to Althorp, Northamptonshire in 1827, the land was sold to John Augustus Beaumont in 1846 and the house was torn down in 1949. (SC)

During the French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars, Wimbledon became a political centre at the highest levels. Because Wimbledon was close to the Portsmouth Road (the A3), access to Portsmouth was easy, which made Wimbledon popular for naval officers. Also, part of the attractiveness of Wimbledon was the prevalent wind from the SW which was invariably free of the pollution that one found in London, particularly during the 18th century. William Pitt the Younger was the Prime Minister during much of this period and he suffered from a lung condition which led his doctors to recommend that he rode his horse away from London for exercise and fresh air. Wimbledon was his frequent destination, only seven miles from Westminster.

Henry Dundas was the Home Secretary and later held the new position of Secretary of State for War. He was a tough Scottish politician who favoured ending the slave trade. He resided in Cannizaro House on Wimbledon Common and was regularly visited by Pitt who arrived on horseback. Also resident on Wimbledon Common was William Wilberforce who was the most important anti-slavery MP. He and Dundas would support each other and then argue and then support each other again until the Slave Trade Act was finally passed in 1807. Pitt also visited Wilberforce regularly and often slept over at his Wimbledon house.

We then have Earl Spencer who was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1794 and his wife Lavinia who resided in Wimbledon Park House, which was regularly visited by Pitt and the leading naval officers of the period including Lord Nelson and his wife Francis. Nelson had two very important naval supporters, Earl St Vincent (Admiral Sir John Jervis) who was Nelson’s commander and Earl Spencer who St Vincent reported to. All was well until Nelson, following his victory at the Nile, became infatuated with Lady Hamilton in Naples. Upon Nelson’s return to England in 1801, and Emma’s buying Merton Place in South Wimbledon, the relationship with Earl Spencer grew frosty as Lavina refused to have anything to do with Lady Hamilton. Nelson became a social outcast, but he cared little as he was more often than not at sea and Emma was the love of his life. It all came to an end at Trafalgar with the death of Nelson in 1805. Pitt passed away in 1806 and Earl Spencer lost his post as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1801, so from there Wimbledon lost its place of importance. Earl Spencer and Lavina moved to Althorp, Northamptonshire in 1827, the land was sold to John Augustus Beaumont in 1846 and the house was torn down in 1949. (SC)

Beaumont was a property developer and started building on the area between Parkside and Wimbledon Park Road. In 1847 he continued with Arthur Road, Leopold Road, Lake Road and Home Park Road.

However, by 1872 the development had not progressed as quickly as he had hoped so he retired. After his death in 1886 his daughter Augusta inherited the estate but took no interest in its beauty and thought only of the potential for developing as much of the land as possible in order to maximize profit. She in fact drew up a plan to drain the lake, build a road to extend Revelstoke Road across the park and build houses upon the whole area.

In the meantime, the railway had arrived and houses started to be built on Kenilworth Avenue and Dora Road. However it was not until 1905 that developers started building on the grid, amongst them being Ryan and Penfold, whose names combined to form Ryfold Road. By 1910, the area was largely developed and there are pictures in the Wimbledon Museum of the roads with nothing more than a milk cart, a far cry from the parking congestion of today! In Bernard Rondeau’s book about Wimbledon Park, there are estate agent details of a house for sale for £600 freehold!

In 1914, Wimbledon Corporation decided to buy what remained of the Wimbledon Park Estate which had escaped development. This was largely in response to the proposal by Augusta Beaumont to completely develop the Park. Parliament had to approve the purchase and there were many in the borough who saw it as a waste of public money, but thankfully for us the purchase of the park was completed.

During the first world war, the area of the park that had been used for polo near Horse Close Wood, was converted to a piggery to help the war effort. There was great hilarity when in 1918, Queen Mary was presented with a pig when visiting the park. There is a photograph of the occasion in the museum, and both are smiling!

Following the move of the All England to Church Road in 1922, the Council decided in 1925 to sell off the area of the Park knows as Banky Field, which is to the east of Home Park Road, to provide the money for the building twenty public twenty tennis courts and the Home Park Road pavilion. This caused an outcry at the time with many objections being raised by local people. However the Council proceeded despite the objections and the houses we now see along Home Park Road were built as a result. The Home Park Road pavilion and the tennis courts were opened to the public in 1926.

The Wimbledon Park Golf Club had been resident in Wimbledon Park since 1898 with Wimbledon Council, subsequently Merton Council, owning the land and leasing it to the Golf Club. This was the perfect use of the land as many of the Capability Brown views were preserved as well as many of the oaks he had planted in the park. Merton Council decided in 1993 to sell off the freehold of the golf course land to the All England Lawn Tennis Club. Despite strong opposition from local residents, the sale went through and the All England bought the freehold for £3.2 million. The golf club lease remained until 2041. At the time of the sale of the freehold to the All England, the All England stated that they had no plans to develop the Golf Club land and purchased the leasehold to ensure there was a green buffer to the east of Church Road to preserve the landscape around the All England.

It was because of the threat of possible development of the golf course land by the new owner, that a number of local residents agreed to form the Wimbledon Park Heritage Group with the object of preserving this historic landscape for the future and to provide improvements to the London Borough of Merton sector to the park; all of which has created a closer relationship between the stake holders, the Council and the local residents.

Unfortunately one has to be aware of what the All England would really like to do and that is gain full control of the parkland which they did on 12 December 2018 by offering each and every member of the Golf Club £85,000 to vote toward relinquishing their leasehold. It was just too much money and for a total expenditure of £65 million pounds, the All England gained control of the 73 acre site.

What will they do with the land? One doesn't know, however, the All England certainly enjoys building projects, and the task of the Heritage Group will be to defend the parkland as much as we can as each building project will require Council planning permission. The park remains a Grade 2* listed park and there are many organizations very interested in preserving what's left of Capability Brown's vision for this wonderful parkland.

Unfortunately one has to be aware of what the All England would really like to do and that is gain full control of the parkland which they did on 12 December 2018 by offering each and every member of the Golf Club £85,000 to vote toward relinquishing their leasehold. It was just too much money and for a total expenditure of £65 million pounds, the All England gained control of the 73 acre site.

What will they do with the land? One doesn't know, however, the All England certainly enjoys building projects, and the task of the Heritage Group will be to defend the parkland as much as we can as each building project will require Council planning permission. The park remains a Grade 2* listed park and there are many organizations very interested in preserving what's left of Capability Brown's vision for this wonderful parkland.

For more information regarding the history of Wimbledon Park, you might wish to read:

Wimbledon Park, from private park to residential suburb. by Bernard Rondeau, published by the author, and available from the Wimbledon Library.

The Spencers in Wimbledon (1744-1794), by Richard Milward MA, published by The Milward Press, and available from the Wimbledon Library and Wimbledon Museum.

Wimbledon, A Surrey Village in maps, by Richard Milward MA and Cyril Maidment, published by The Wimbledon Society Museum, and available from both the Museum and Wimbledon Library.

Wimbledon Park Heritage Group